How Game Translation Caused a Pokémon Protest (And How to Avoid It in the Future)

In Hong Kong this May, around 20 protesters marched to the Consulate-General of Japan to rally against Pikachu’s name change.

Yes, you read that right. Pikachu. As in, the Pokémon. The name change of a Pokémon caused a group of Hongkongers to protest at the Japanese consulate.

What happened here? You might think it’s another funny meme about the recently released game Pokemon Go — but believe it or not, this is an actual news item. It’s actually also a great lesson on translation, and the complications of working with the Chinese language in particular. In this blog post, we’ll explain what happened in Hong Kong, and guide you through some best practices for localizing your game for Chinese-speaking regions—so you can be sure that you’re not the cause of the next rally.

But first, some context.

Nintendo decides on a unified Chinese localization…

In late February of 2016, Nintendo announced the upcoming release of the seventh generation of the Pokémon series, Pokémon Sun and Moon. In this generation, Nintendo has added Chinese (both Traditional and Simplified), making the game available in nine languages.

The decision to localize in Chinese was wise; Nintendo is clearly targeting the huge gaming markets in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. But Nintendo also unified the translation of the game title and its characters—which was a lot less wise.

After all, there are pros and cons to unifying the localization. The pros are pretty obvious. Unification cuts translation costs, and it allows the company to use the same marketing content and graphics for multiple markets. Unification also makes it easier to ensure that the proper terminology is being used, thereby reducing the chance of having Pokémon characters end up with the wrong names. Many fans have strong childhood memories of the game, so it’s best if change can be minimized.

And that’s where the protest comes in. Unification is a good idea—as long as it doesn’t change the different localizations that had been used previously. Fans in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan had grown up with three different versions of Pokémon: different animations, different TV shows, different comics, and different names. Players in these three markets have all had their own understandings of Pokémon. And changes to that understanding are not welcome.

…but Chinese localization can be tricky

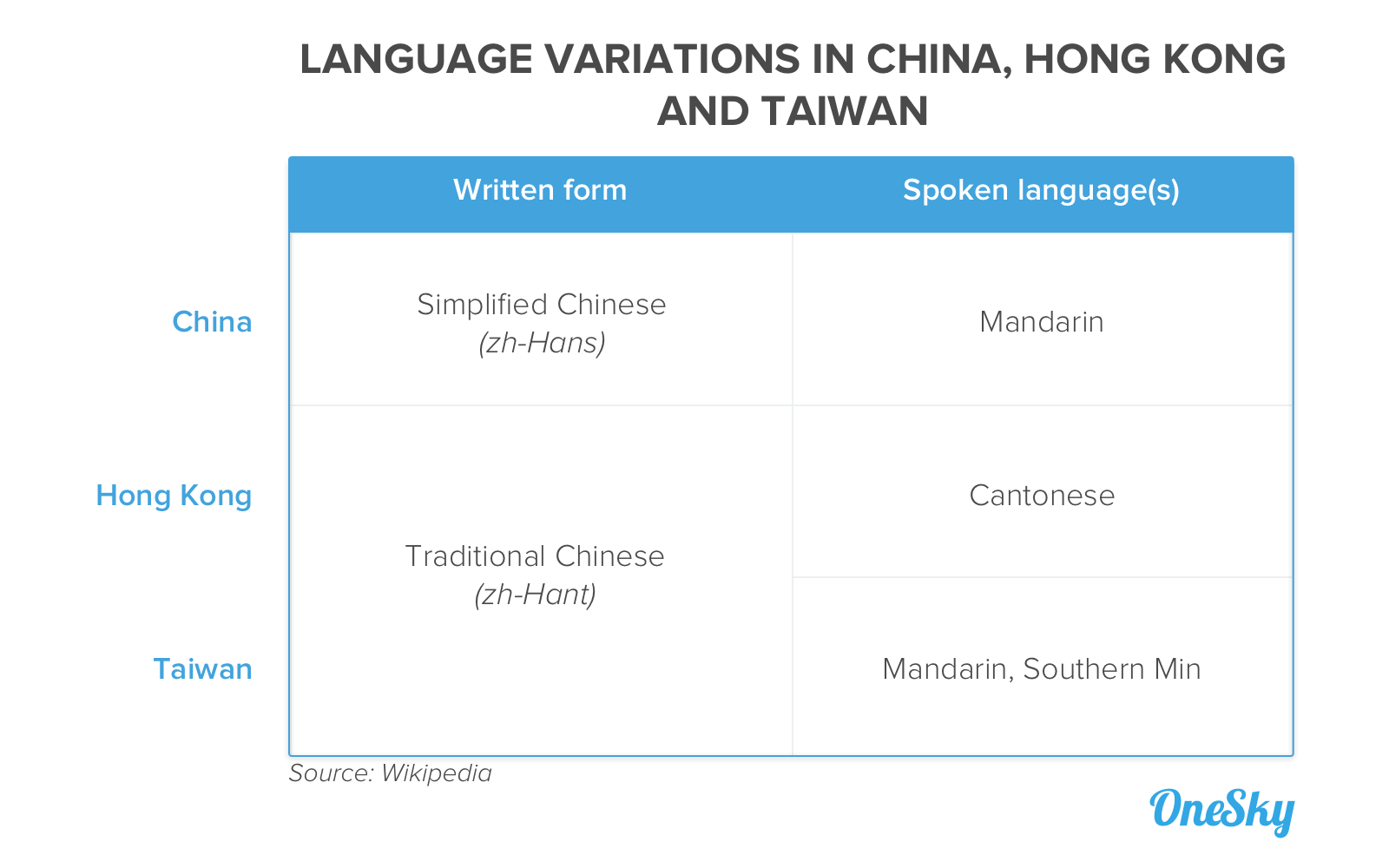

The graphics weren’t the only problem—it was also the language itself. Although all three markets speak and write in Chinese, there is huge variety. Hongkongers speak Cantonese. Taiwanese speak Mandarin, but with an accent that is vastly different from the one used in China. Traditional characters are used in Hong Kong and Taiwan; simplified characters are used in China. The graph below illustrates the language variance in the three territories.

So, when Nintendo released Pokémon with a unified localization, Hongkongers found themselves suddenly faced with a very different product.

Let’s go back to Pikachu. In the translation the players were used to, the character was called “Bei Ka Chiu.” But now, it’ll be “Pei Ka Yau” releasing those electric thunderbolts.

For long-time Pokémon devotees, that just feels wrong. In front of the consulate, the Hong Kong protesters tore up the new names being used by the Pokémon franchise and tried to deliver a letter to the Japanese Consul-General. And, when a petition was created in March, requesting that the names be switched back to their Hong Kong versions, over 6,000 people signed it.

How Nintendo reacted

Nintendo decided not to back down. They’ve stood by the unified translation, and have tried to resolve the conflict by promoting the English pronunciation as a compromise. Regardless of whether Pokémon lovers spoke Cantonese or Mandarin, Nintendo encouraged them to just say “Pikachu,” in a statement released by the company’s Hong Kong office shortly after the protest.

But they must have realized this alone wouldn’t cut it. In order to avoid confronting protesters, Nintendo also postponed many of the promotional activities scheduled to take place in Hong Kong, including the 2016 Pokémon World Championships.

Four lessons to learn from this

1. China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are three vastly different markets

The markets may all use the same language, but that doesn’t mean they’re the same. When working with these areas, it’s important to recognize that you’re dealing with three very different cultures—and business patterns as well. China, for example, uses unique distribution channels. The three places each have their own slang. Hongkongers and Taiwanese each have different favorite social networks. And that’s all just the tip of the iceberg.

If you want to know more about these three markets, check out our blog posts about mobile gaming in China and in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

2. Targeting your audience pays off

It’s Marketing 101: keep your messages sharp and specific. That’s how you engage the audiences you want, when you want them. The same principle applies to localization—when your budget allows, localize for the language that your audience really uses, rather than a generic translation.

Players from Chile and Spain don’t speak the same version of Spanish, so use Latin American Spanish when you enter Chile. And, as Nintendo learned, localize into Cantonese if you want to really reach the Hong Kong market.

3. Start to manage your translation glossary early, and stay vigilant

When Nintendo unified the localization, they did it too late. Previously, localization had been handled by the local distributors of the Pokémon franchise. This meant that there wasn’t official, across-the-board terminology established for the game characters.

These variations were one of the reasons they decided to unify the localization. But the variations were the reason that the localization failed.

It’s an important lesson. When your game or your product is just beginning the process of localization, you need to create a translation glossary to ensure that you have (and keep!) ownership. Brand names—and any other names related to your product—are important assets of your company, and a translation glossary is how you ensure that these names stay consistent for your product, whether it’s being used in Taiwan or Tennessee. It’s okay to leave your translation vendors to handle most of the translation. But you have to make sure that the results are consistent.

Don’t know how to build a translation glossary? Check out this blog post for more.

4. Resolve translation issues quickly

It might sound absurd that a small translation shift could lead to a political protest. But language is important, and translation choices are often controversial. Nintendo is not the first company to run afoul of this issue; an IKEA mistranslation also once ended up as a political flashpoint.

Luckily, IKEA handled the scandal well, and so can you. Never treat translation errors as trivial. If your company receives a complaint about a translation, fix it. Quickly.

Wrap up

So, how do you localize well? It’s more than just knowing your markets (although that’s definitely part of it!). For an intro to the ins and outs of game localization, download our eBook. And, if you have any thoughts on translation errors—or a story of your own—please let us know in the comments section.

//

Written by -

Written by -

Written by

Written by

wow its so nice article and Blog i like this Blog so much

Happy New Year 2017

Happy New Year Cover Photo

New Year Cover Photo For Facebook

Happy New Year images Wallpapers